Imagine a world where the roar of a tiger echoes through eucalyptus forests, or where koalas munch leaves while rhinos graze nearby. It sounds like something out of a fantastical nature documentary, doesn’t it? But here on Earth, such a meeting is simply impossible. For centuries, naturalists and explorers marvelled at a perplexing invisible divide in Southeast Asia, one that perfectly separated the creatures of two vastly different worlds. They called it the Wallace Line, and its secret has finally been laid bare.

The Invisible Divide: A Tale of Two Faunas

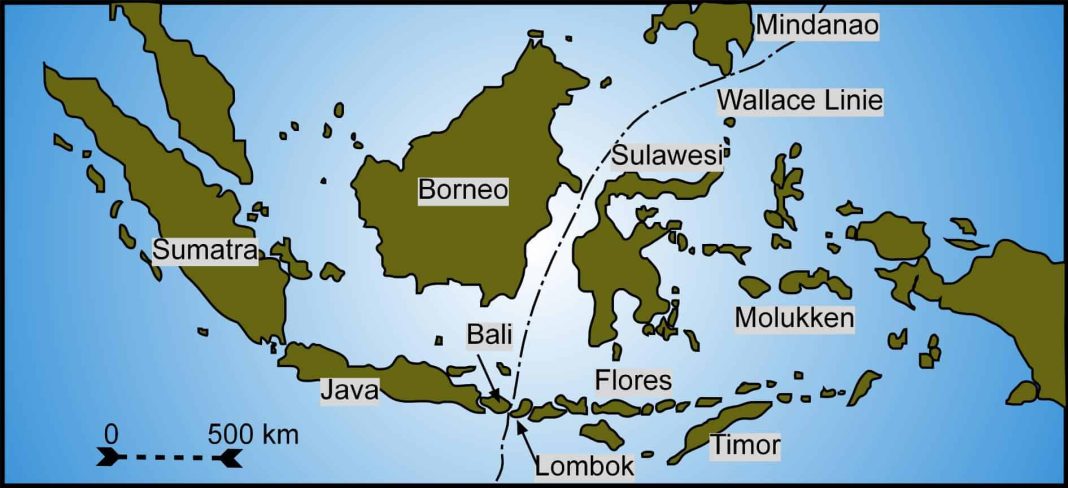

Picture the islands of Southeast Asia – a vibrant mosaic of land and sea. To the west, you find animals distinctly Asian: tigers in Sumatra, elephants in Borneo, rhinos, and monkeys galore. Venture just a short distance east, and suddenly the landscape changes, not in appearance, but in its inhabitants. You’re now in the realm of marsupials and monotremes: kangaroos, koalas, cockatoos, and cassowaries. It’s a jaw-dropping shift, occurring over distances sometimes as narrow as 35 kilometres between islands like Bali and Lombok.

Alfred Russel Wallace, the brilliant contemporary of Darwin, was the first to meticulously document this extraordinary biological boundary in the mid-19th century. He noticed that islands west of the line shared biological traits with mainland Asia, while those to the east harboured species more akin to Australia. This wasn’t merely a gradual transition; it was a stark, almost instantaneous change. For decades, scientists pondered: what force could possibly create such an absolute, invisible barrier?

Unveiling the Ancient Secret: A Deep Ocean Story

The “secret” of the Wallace Line isn’t a magical force field or an ancient curse. It’s far more profound and rooted in the deep history of our planet: plate tectonics and fluctuating sea levels. Unlike other land bridges that formed and disappeared with ice ages, the Wallace Line represents a persistent, deep oceanic trench that has remained submerged for tens of millions of years. This trench runs through what is known as the Sunda Shelf (to the west) and the Sahul Shelf (to the east).

During glacial periods, when vast amounts of water were locked up in ice caps, global sea levels dropped dramatically – sometimes by over a hundred metres. This exposed vast swathes of land, connecting islands like Sumatra, Java, and Borneo to mainland Asia, allowing Asian species to spread across what became known as Sundaland. Similarly, to the east, New Guinea and Australia were linked, forming Sahul, enabling marsupials and other unique Australian fauna to roam freely.

However, the crucial insight is this: the Wallace Line itself, specifically the deep water between the Sunda and Sahul shelves, remained stubbornly submerged. Even at its lowest, the water was too deep to ever form a land bridge. This deep-water barrier prevented the intermingling of the two distinct faunas. “It’s truly a testament to geological time,” explains Dr. Elara Vance, a biogeographer. “Those deep trenches were insurmountable barriers for millions of years, even when vast continental shelves were exposed. It dictated evolution itself.” This constant separation allowed Asian and Australasian species to evolve independently, creating the two distinct biological provinces we observe today.

The Enduring Legacy of an Invisible Wall

The Wallace Line is more than just a line on a map; it’s a profound demonstration of how geological history shapes the very fabric of life on Earth. It tells a story of continental drift, ancient oceans, and the relentless march of evolution, all converging to create a biological boundary unlike any other. Knowing its secret only deepens our appreciation for the intricate dance between geology and biology.

So, while tigers will forever prowl the jungles of Asia and koalas will cling to their eucalyptus trees in Australia, we now understand why they will never meet. The invisible barrier, a testament to Earth’s ancient past, has ensured their separate destinies, making our world a richer, more diverse, and endlessly fascinating place.