The sky darkens. Birds fall silent. A celestial shadow creeps across the sun, turning day into an eerie twilight. For ancient civilizations, a solar eclipse was often a terrifying omen, a sign of divine wrath or cosmic disruption. But for the Maya, it was something else entirely: a predictable event, meticulously charted and understood centuries in advance. How did this incredible civilization, without telescopes or modern computing, achieve such profound astronomical insight? The answer lies in a blend of relentless observation, sophisticated mathematics, and an unparalleled dedication to the cosmos.

A Sky Full of Secrets, Carefully Unlocked

The Maya weren’t just casual stargazers. They were systematic, patient astronomers who spent generations tracking the movements of the sun, moon, and visible planets. Their priests and scribes painstakingly recorded celestial events over hundreds of years, building an immense library of observational data. They understood that the heavens operated on discernible cycles, and their focus wasn’t just on solar eclipses, but also lunar eclipses, which occur more frequently and are visible from a wider area. Observing lunar eclipses helped them identify the patterns and periods that govern all eclipse events. This was a crucial foundational step in their larger predictive model.

Their advanced numerical system, including the concept of zero, and their intricate calendar systems (like the Long Count, Tzolkin, and Haab’) were not just for measuring time, but for mapping these cosmic rhythms. Imagine the sheer dedication required to spot recurring patterns in movements that span decades and even centuries, all with the naked eye and precise positional measurements from observatories built for this very purpose. “Their ability to track these complex celestial ballet moves without modern instruments is a testament to extraordinary dedication and intellectual curiosity,” notes Dr. Elena Ramirez, a leading archaeoastronomer. This wasn’t guesswork; it was empirical science, millennia before the term existed.

The Dresden Codex: Blueprint for the Cosmos

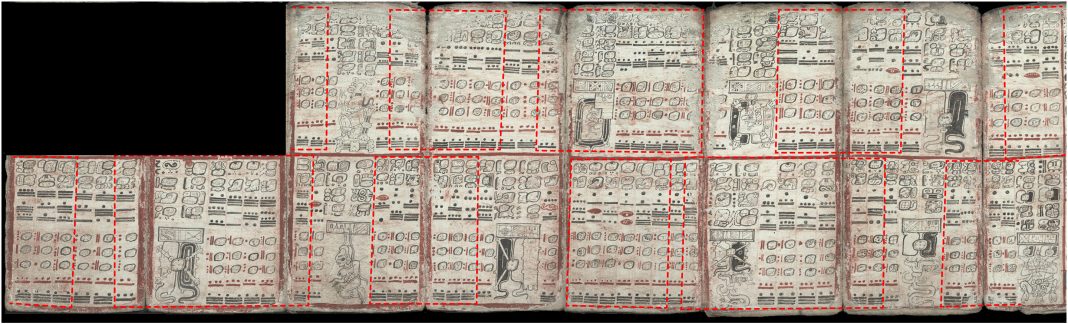

The pinnacle of Mayan astronomical achievement is perhaps best showcased in texts like the Dresden Codex. This ancient book, one of the few surviving Mayan codices, contains what scholars refer to as an “eclipse table.” Far from a simple prediction, this table is a highly sophisticated instrument for identifying when eclipses were possible. It doesn’t pinpoint the exact geographical location of every eclipse, but it accurately predicts the windows of time when both solar and lunar eclipses could occur.

The Maya understood the underlying mechanism behind eclipses: the rhythmic alignment of the sun, Earth, and moon. Crucially, they grasped the concept of the saros cycle – a period of approximately 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours after which the sun, Earth, and moon return to very nearly the same relative positions, resulting in a practically identical eclipse. By meticulously tracking these 5,842-day cycles over centuries, they were able to forecast future eclipses with astonishing accuracy. They identified specific dates within these cycles where eclipses were highly probable, allowing them to prepare both ritually and practically for these awe-inspiring events.

Conclusion

The Maya’s mastery of eclipse prediction wasn’t magic; it was the product of remarkable intellect, relentless observation, and sophisticated mathematics. Their profound understanding of celestial mechanics, etched into stone and parchment, stands as an enduring testament to human ingenuity. They remind us that even without modern technology, a deep connection to the natural world and a commitment to understanding its patterns can unlock the universe’s most profound secrets. Their legacy continues to inspire, revealing a civilization not just of monumental architecture, but of monumental scientific achievement, forever intertwined with the dance of the cosmos.