The political landscape of Bihar once again took center stage as the results for the 2025 Assembly Elections were declared, handing a decisive mandate to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). Amidst the celebrations and post-mortem analyses, veteran political leader Sharad Pawar offered a critical and rather controversial perspective on the NDA’s victory, attributing their success significantly to an alleged ₹10,000 payout to citizens, which he termed a “corruption of sorts.” This statement has ignited a fresh debate on electoral ethics, welfare schemes, and the purity of the democratic process in India.

NDA Secures Decisive Mandate in Bihar 2025

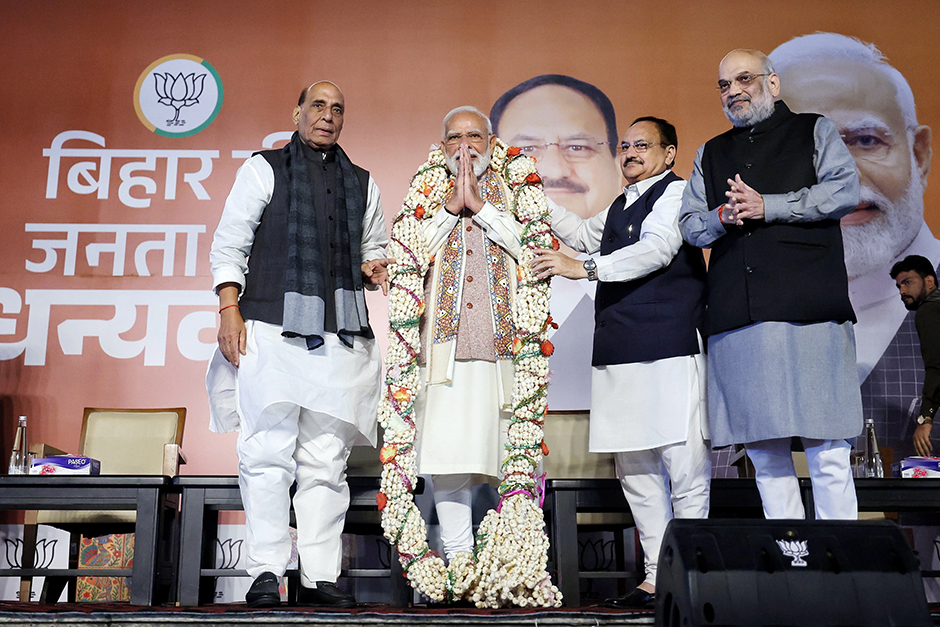

The Bihar Assembly Elections 2025 culminated in a resounding victory for the NDA, comprising the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Janata Dal (United) JD(U), and other regional allies. The alliance successfully crossed the majority mark, securing a comfortable lead over the opposition Mahagathbandhan (Grand Alliance) led primarily by the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the Congress. The results reflected a strong consolidation of votes in favor of the incumbent coalition, defying some exit poll predictions and pre-election speculations that had hinted at a closer contest.

Political analysts pointed to several factors contributing to the NDA’s success, including the charismatic leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the ground-level organizational strength of the BJP, and the perceived stability offered by the Nitish Kumar-led government in the state. Welfare schemes implemented by both central and state governments were widely believed to have played a crucial role in garnering public support. The NDA’s campaign focused heavily on development, good governance, and nationalistic sentiments, resonating with a significant portion of the electorate, particularly women and youth voters, who often form a critical swing vote bloc in Bihar.

Sharad Pawar’s ‘Corruption of Sorts’ Allegation

In the aftermath of the Bihar election results, Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) chief Sharad Pawar, known for his astute political observations, weighed in with a pointed remark that quickly drew national attention. Speaking to reporters, Pawar suggested that the NDA’s victory was not solely a reflection of public sentiment towards their policies or governance, but was significantly influenced by financial disbursements. He specifically referenced an alleged ₹10,000 payout that purportedly reached households just before the elections.

Pawar stated, “It is clear that the NDA’s success in Bihar cannot be seen in isolation from the direct ₹10,000 payout that reached many households just before the polls. While presented as welfare, such a distribution close to an election certainly raises questions and, in essence, amounts to a corruption of sorts, swaying voters with direct cash rather than genuine policy.” His comments imply a blurring of lines between legitimate government welfare initiatives and electoral inducements, challenging the sanctity of the mandate.

The veteran leader’s remarks have opened a Pandora’s Box, inviting discussions on the ethics of direct benefit transfers (DBT) and other financial aid schemes when implemented in close proximity to elections. While governments often launch and highlight welfare programmes, the timing and quantum of such payouts become contentious issues, especially when opposition parties perceive them as an attempt to influence voters rather than a genuine social security measure. This perspective suggests that while such actions might technically remain within legal boundaries, their spirit could undermine free and fair elections by financially incentivizing votes.

The Broader Debate on Welfare and Electoral Ethics

Pawar’s “corruption of sorts” comment taps into a long-standing debate in Indian politics: the distinction between welfare measures and electoral freebies. Political parties across the spectrum have often been accused of using financial incentives, whether direct cash transfers, subsidized goods, or loan waivers, to woo voters. The Election Commission of India (ECI) has, over the years, introduced various guidelines and model codes of conduct to curb such practices, especially during the election period. However, the exact definition of what constitutes an “inducement” versus a “welfare scheme” often remains a grey area.

For proponents of welfare schemes, such payouts are crucial for social upliftment and poverty alleviation, representing the state’s commitment to its citizens. For critics like Pawar, when these schemes are strategically timed and heavily publicized just before polls, they risk distorting the electoral process, compelling voters to prioritize immediate financial gain over long-term policy considerations or governance quality. The Bihar results, viewed through Pawar’s lens, are not just a reflection of political popularity but also an outcome of tactical financial interventions that, according to him, constitute a subtle form of corruption that undermines democratic principles.

Conclusion

The NDA’s victory in the Bihar Assembly Elections 2025 firmly establishes their dominance in a crucial Hindi heartland state, setting the tone for future political contests. However, Sharad Pawar’s candid assertion about the ₹10,000 payout being a “corruption of sorts” casts a shadow of controversy over the mandate. His remarks underscore the persistent ethical dilemmas surrounding welfare schemes and their potential impact on electoral outcomes in India. As the political discourse evolves, this debate is likely to intensify, prompting closer scrutiny of financial inducements and their role in shaping the democratic fabric of the nation.