The cosmos is a vast, enigmatic canvas, constantly surprising us with new brushstrokes of discovery. Just when we think we’ve charted a familiar territory, something unexpected pops up, challenging our perceptions. The latest buzz from the astronomical community involves a Saturn-sized planet making an appearance in what scientists affectionately, or perhaps despairingly, refer to as the “Einstein desert.” This isn’t a literal desert of sand and dunes, but a region of space where detecting certain types of exoplanets has historically been exceptionally challenging. The implications of this discovery are profound, reshaping our understanding of planetary distribution and the very tools we use to find them.

Understanding the ‘Einstein Desert’

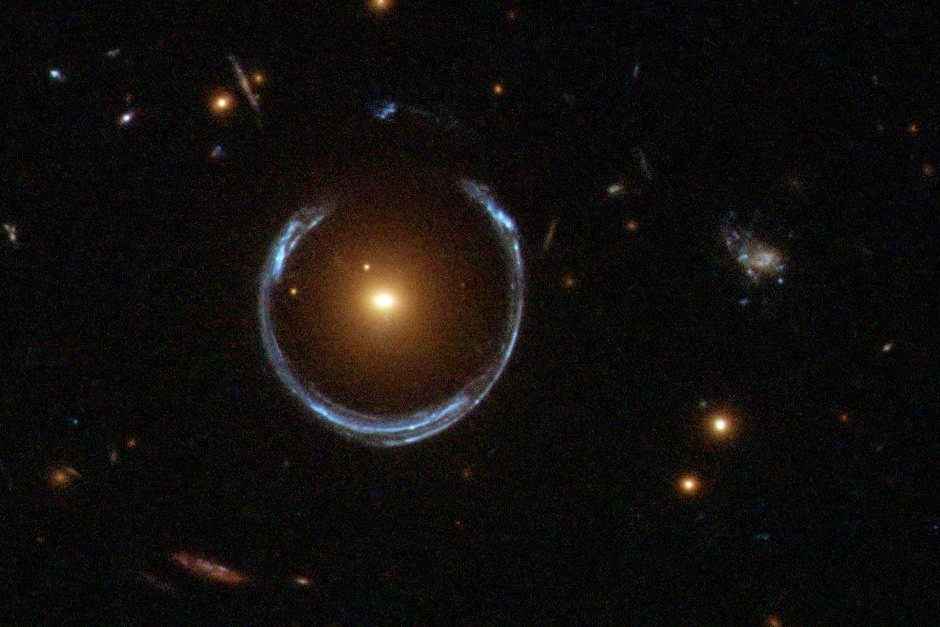

To grasp the significance of this discovery, we first need to understand the “Einstein desert.” This term refers to a particular blind spot in exoplanet detection, especially for planets found using gravitational microlensing. Gravitational microlensing is a powerful technique rooted in Einstein’s theory of general relativity, where the gravity of a foreground object (a star or planet) acts like a cosmic magnifying glass, bending and brightening the light from a more distant background star. This temporary brightening can reveal the presence of otherwise invisible planets.

While incredibly effective for finding gas giants orbiting far from their host stars, or smaller, Earth-like planets closer in, the method has struggled to reliably detect planets with masses similar to Saturn or Neptune, orbiting at intermediate distances from their stars – analogous to Saturn’s orbit in our own solar system. This region, where a planet’s mass and orbital distance fall into an observational sweet spot that makes detection via microlensing difficult, became known as the “microlensing desert” or, more broadly, the “Einstein desert,” acknowledging the fundamental principle at play. It was less an empty space and more a difficult-to-observe one, leaving a gap in our planetary census.

An Oasis in the Desert: The Saturn-Sized Discovery

The recent detection of a Saturn-sized exoplanet in this previously barren observational zone is nothing short of a scientific landmark. This new world, identified through a meticulous analysis of microlensing data, challenges the notion that such planets are rare in these orbital configurations or simply too elusive to spot. Its emergence suggests that our previous observational limitations, rather than an actual scarcity of planets, might have been the primary reason for the “desert.”

The precision required for such a find highlights the growing sophistication of our observational techniques and data analysis. It indicates that the tools are improving, allowing us to push the boundaries of what’s detectable. As Dr. Elena Petrova, a theoretical astrophysicist, remarked, “This discovery really opens our eyes to the hidden diversity of planetary systems out there. It’s a testament to how microlensing, when pushed to its limits, can reveal planetary populations we might otherwise miss entirely.” This breakthrough offers a tantalizing glimpse into a population of planets that could be far more common than our current exoplanet catalogs suggest.

Implications for Planet Formation and Distribution

The presence of a Saturn-sized world in the Einstein desert has profound implications for theories of planet formation and orbital dynamics. Current models often predict certain distributions of planet types at various distances from their stars. This new discovery compels us to re-evaluate those models, particularly concerning the prevalence and formation mechanisms of intermediate-mass planets. Are these planets formed differently, or do they migrate into these orbits in ways we hadn’t fully appreciated?

Furthermore, this finding invigorates the search for similar worlds. If the “desert” is starting to bloom with life-sized planets, it suggests that future, more sensitive microlensing surveys could uncover a wealth of hitherto undiscovered exoplanets. It validates the ongoing investment in ground-based observatories and space telescopes dedicated to microlensing, promising a richer, more complete understanding of planetary demographics across the galaxy. The universe, it seems, is always more populated and varied than our current instruments might suggest, waiting for us to refine our gaze.

The appearance of a Saturn-sized planet in the “Einstein desert” isn’t just an isolated astronomical event; it’s a paradigm shift. It tells us that our universe is likely teeming with more planetary variety than we’ve been able to detect, and that our investigative tools are continually evolving to match its complexity. This discovery serves as a powerful reminder that every new observation has the potential to rewrite chapters in our cosmic story, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge ever further into the unknown.